Annex E: Battle of the Angrivarian Wall

E.1 The information availabe for the localization of the Battle of the Angrivarian Wall

Shortly after the Battle of Idistaviso, which according to the Roman writer Tacitus took place near the Weser, according to Tacitus between the Ems and Weser there was the Battle of the Angrivarian Wall:

“At last they fixed on a position pent in between a stream and the forests, with a narrow, waterlogged plain in the centre; the forests too were encircled by a deep swamp, except on one side, where the Angrivarii had raised a broad earthen barrier to mark the boundary between themselves and the Cherusci.”

About the purpose of this building today there are conflicting views. It is believed that it is this was a pre-historic border fortifications between Angrivarii and Cherusci. However, this wall would be the only known, like a wall protected boundary that had existed between the two Germanic tribes at this time. However from this viewpoint it is also conceivable that this wall was only built in conjunction with the campaign of Germanicus, to fulfill a strategic role within the tactics of Arminius. (Wikipedia: Angrivarierwall)

It is also doubtful whether the Angrivarii could have operated such a border wall. Angrivarii and especially the Cherusci were no small tribes, correspondingly huge were their territories, and correspondingly huge was their common border (provided that this was even fixedly defined), 30 km to 50 km this border would have been long at least. An effective border fortification therefore should have been also at least 30 km to 50 km long, as the Cherusci could have bypassed a shorter border barrier with only one day’s march otherwise. An effective border fortification also would have needed to be constantly monitored, the organization of the guards would have been a not to be underestimated challenge for the Angrivarii. Furthermore it argues against the role of Angrivarian Wall as a border wall, that it is very unlikely that the remains of a 30 to 50 km long border fortification were not found until today.

A strategic function of the Angrivarian Wall in the context of a battle between Germanicus and Arminius is therefore much more likely. As described above, the Battle of the Angrivarian Wall took place between Ems and Weser. As a Roman legion could not move freely in Germania but had to rely on existing ways, the Angrivarian Wall would have been located at a protohistoric highway system between the Ems and Weser.

An important chain of evidence to find the Battle of the Angrivarian Wall is therefore a Roman-Germanic battlefield at a protohistoric highway between Ems and Weser, in which a wall has played an important role.

A trading route known since the antiquity that meets this criteria is the ‘Hellweg unter dem Berg‘. The ‘Hellweg unter dem Berg’ passes north of the Weser Uplands and south of the vast swampy flat zones of Lower Saxony, and leads from Minden across the Ems to the Netherlands.

Fig. E.1-1: Protohistoric highway ‘Hellweg unter dem Berg’ (brown) in relation to Ems (light blue) and Weser (dark blue)

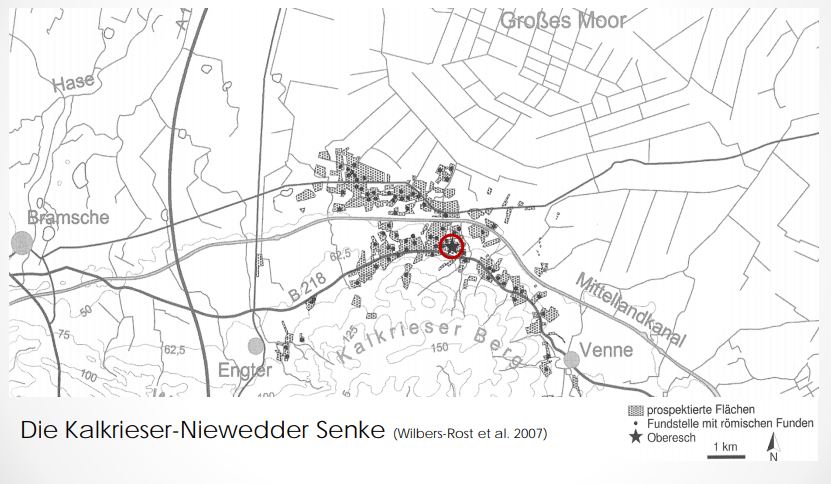

At the ‘Hellweg unter dem Berg’ in 1987 a Roman battlefield was discovered in the Kalkriese-Niewedde depression by the British officer and detectorist Major Tony Clunn, the so-called find-region Kalkriese. Due to a result-oriented finding interpretatio Kalkriese is associated with the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, a theory independent of finds that derives Kalkriese as place of the Varusschlacht however does not exist. Since many factors influence the conservation of artifacts in the soil (eg soil texture, agricultural use in recent centuries), the theory development for a singular event such as a battle only on the basis of finds is highly dependent on coincidence, with the regarding negative consequences for the reliability of the scenario developed for the events at Kalkriese.

No coins were found in Kalkriese that have been coined after 1 AD (Gaius-Lucius coins as closing coins, embossing period 2 BC to 1 AD) or that probably were counterstamped by Varus between 7 and 9 AD (asses with the mark VAR), and pits, in which human bones (which previously had been at the surface for some time) and mule bones were deposited, are put into context with the grave mound built by Germanicus for the fallen of the Teutoburg Forest Battle as described by Tacitus.

However bones of men together with bones of mules in a hastily built pit have little to do with the state funeral which was reported by Tacitus. Without the assumption that Kalkriese is one of the places the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, according to the opinion of the author no one would have had the idea that with the so-called bone pits the last respect was paid to Roman legionaries.

Also the fact was that from over 2000 coins found in Kalkriese none was coined after the Teutoburg Forest Battle although 8 legions of Germanicus searched the Varus battlefield, and the presence of a Roman legion normally is always associated with coin finds, would mean that also the Germanicus-legions had no money which was coined after the Teutoburg Forest Battle. This would in turn mean that because of the terminating date 9 AD it is not to decide whether the coins in Kalkriese were lost by Varus legionaries or by Germanicus legionaries.

Kalkriese bottleneck: superposition of several events

Furthermore, in Kalkriese unusually many hoards of coins were discovered (hitherto 7 hoards), lastly a hoard of 200 silver coins. This would be too much for an amount of money carried by a legionary, but too little for a legion’s cash. It would, however, correspond to the amount of money a civilian, such as a Roman trader, carried with him.

Also the glass eyes found in Kalkriese (Roman glass eyes from Kalkriese) indicate a civilian context. The glass eyes are very inhomogeneous in terms of the glass used and the production technique, which indicates a stock of a craftsman or an artist used for the production of furniture or statues or busts, which are all clearly not military products.

Together with the high number of finds of civilian or sacred objects in Kalkriese, it occurs that two or more events have contributed to the overall findings of Kalkriese: a military event which explains the weapons and a civilian event which explains with the coins and the other civilian and sacred objects. The civilian event could be an attack on a Roman refugee trek.

Result of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest: migration

The Roman historian Cassius Dio reports about Roman city foundations in Germania: “Cities were founded and the barbarians adapted to the Roman way of life, visited the markets and held peaceful gatherings". In these cities, therefore, mainly Germani lived in an early stage of Romanization, but also Romans lived there, for example traders or people have worked in administration. Under Varus’ govenorship a too rapid a transformation of Magna Germania into a completed Roman province led to an increasing upset or even hate of the Germani on the Romans who were now regarded as occupiers. As a consequence, in the spring of the year 10, when the Roman legions did not return east of the Rhine and could no longer offer protection, the Romans in Magna Germania were not safe any longer and they had to flee: the result of the battle of the Teutoburg Forest caused migration in Germania.

As discussed in chap. 1 Roman cities were embedded in an agrarian environment, which supplied the cities with food. A very good location would be as also discussed in chap. 1 the Hildesheim Boerde, so very likely a Roman city was founded there. Since in the Hildesheim Boerde there aren’t any Roman traces, the Roman city must be under roof today, thus today’s Hildesheim could have its origins in the Roman city foundation.

For the escape of the Romans from Hildesheim to the west towards the Rhine, the abovementioned ‘Hellweg unter dem Berg’ was the shortest connection. Since the escape of the Romans, who were wealthy in some cases, were not unnoticed by their Germic neighbors, the danger of robbery resulted for the refugee trek, a good place to intercept the refugees was the bottleneck of the Hellweg at Kalkriese. And in these attacks on the Roman refugees in the year 10, most of the coins found in Kalkriese also came into the ground. This might be because at the attacks the copper coins (aces) which were valueless for the Germani were thrown away, and only silver coins and gold coins were kept, or because some Romans had buried more valuable coins as a hoard when Germanic groups approached, to possibly recover these coins later.

In the context of the escape from the Roman city foundation at Hildesheim probably also the Hildesheim Treasure came into the ground, a hoard of silverware, with engraved user names showing that several pesons deposited their valuables together in the hoard, in order to recover them on their return to Hildesheim.

As discussed below, a battle between Romans and Germani took place at the Kalkrieser bottleneck in the year 16, during which the weapons came in the ground. As part of the preparations for the battlefield, the remains of the Romans killed during the robbery of the year 10, were buried, today’s bone deposits with the eye-catching animal bones addition.

Animal bones as grave content are known from the Gallo-Roman culture group, e. g. from the burial ground of Wederath-Belginum. According to G. Mahr, the custom of adding animals or parts of animals as food in tombs has been transferred from the celtic area on the left bank of the Rhine to the right bank of the Rhine, s. Mahr, G., 1967: Die Latènekultur des Trierer Landes. Berliner Beitr. Vor- u. Frühgeschichte 12 (Berlin 1967). Therefore a result-open find interpretation includes the scenario, that Gallo-Roman auxiliary soldiers who accompanied a Roman refugee trek to the west in the year 10 and were killed in a Germanic raid. Gallo-Roman veterans who, as discussed in Chap. 1.5, fought in the year 16 on the side of the Germani, recognized the remains of their countrymen at the battlefield preparation and buried them. This would explain the presence of animal bones in the bone deposits.

However in Kalkriese also a 400 m long wall construction was discovered at the find site Oberesch, which apparently had a strategic role for the battle of Kalkriese.

Fig. E.1-2: Reconstructed section of the Kalkriese Oberesch wall construction, CC BY-SA 3.0

But since in none of the ancient sources reporting about the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest such a wall construction is mentioned, it is relatively unlikely that the find region Kalkriese is related to the Teutoburg Forest Battle. And as the above criteria for battle of the Angrivarian Wall (a wall construction important for a battle at a prehistoric road between the Ems and Weser) are met at Kalkriese, it is very much likely that the find region Kalkriese is the location of the Battle of the Angrivarian Wall.

In a literal interpretation of Tacitus the Kalkriese-Niewedde depression is not quite exactly with Tacitus’ description of the battle field of the Angrivarian Wall. However, Tacitus was not an eyewitness of the battle and dependent on information from second or third hand, and Tacitus’ informants have not necessarily had Tascitus’ accuracy claim. Thus if one abstracts Tacitus’ description of the battle field of the Angrivarian Wall in order to minimize the error potential always latent existing in ancient sources, there is an approximate, that the environment of the battlefield consisted of a stream, a forest and wetlands, and that Angrivarii and Cherusci were there in a geographical relation to a wall-like construct, which matches with the conditions of the Kalkriese-Niewedde depression. In the end, the the most relevant detail from Tacitus’ description of the battlefield at the Angrivarian wall is the wall constructed by the Germani, for which, as discussed above, a tactical function is much more likely than a strategic function; with topographical details from 2000 years old Roman descriptions of Germania always a certain skepticism is appropriate, because they can serve stereotypes, or shall simply decorate the narrative (a river produces in the ‘head cinema’ of the reader better pictures than a creek).

Supplement 2019: Currently (since 2017), due to the discovery of another wall further (system of wall and V-trench, typical trench-wall system of a Roman fieldcamp) north the Wall on the Oberesch is discussed historically as the southern wall of a Roman field camp, which was adapted to the topography of the Kalkriese hill and therefore had a curved shape. However, this inevitably raises the question, if it was a Roman camp wall, why the Romans laid it at the foot of the Kalkriese hill, where one could shoot from the top of the mountain almost unhindered and with good sight with bow and arrow into the camp? The Limeskastell Osterburken shows that it is very unfavorable to build a camp or fort at the foot of a slope. When the threat situation on the Limes increased at the end of the 2nd century and Germanic attacks intensified, the main fort was expanded up the slope to include an annex fort, so that the main fort could no longer be shot at from above.

It raises furthermore the question why the Oberesch wall had a curved shape? A straight wall could be staked out with a line and was therefore much faster to build, and it was also easier to defend because one could see the entire wall section. Furthermore, the Oberesch Wall was stabilized with piles, at which probably also a parapet made of branches was attached.

In addition, the wall was bombarded with bolts. The author considers it very unlikely that the Romans had at the end of the Teutoburg Forest Battle still functioning torsion guns, also the use of such guns within a field camp had for the defense of a wall section also had not made sense, the risk of ‘friendly fire’ would have been very high. And while the space available to the legionaries in a standardized, approximately rectangular field camp was to calculate quickly, the space of a camp with curved walls had to be calculated time-consuming.

In summary it should be noted that it is currently being scientifically examined whether the northern wall standardized for a fieldcamp belongs to the Oberesch Wall, which seems almost experimental as a fieldcamp wall. The building of such an unusual field camp under battle conditions however would be contrary to all reason, thus the author considers the interpretation of the Oberesch wall as a Germanic fortification of the Kalkriese bottleneck as much (much) more meaningful. The author also advises to move from a too result-oriented find interpretation to an open-ended theory construction. This would give new impetus to research in Kalkriese, and would certainly also make public research funding more equitable.

E.2 The course of the Battle of the Angrivarian Wall

Coming from Idistaviso at the Weser Germanicus marched with his legions on the ‘Hellweg unter dem Berg’ westwards. At Kalkriese there was between the Venne peat bog and the Kalkriese hill a natural narrow, which in addition Arminius also had let fortified by the Oberesch wall construction, at which certainly the whole Kalkriese mountain was occupied by Germanic warriors. At the narrow Arminus countered the Romans with his main force. Due to the narrow the Romans could not form up in full extent and were first of all at a disadvantage.

Fig. E.2-1: Battle of the Angrivarian Wall initial situation, advance of the Romans (blue), positions of the Germani (red), Oberesch wall construction (brown), peat bog (yellow), Kalkriese hill (green)

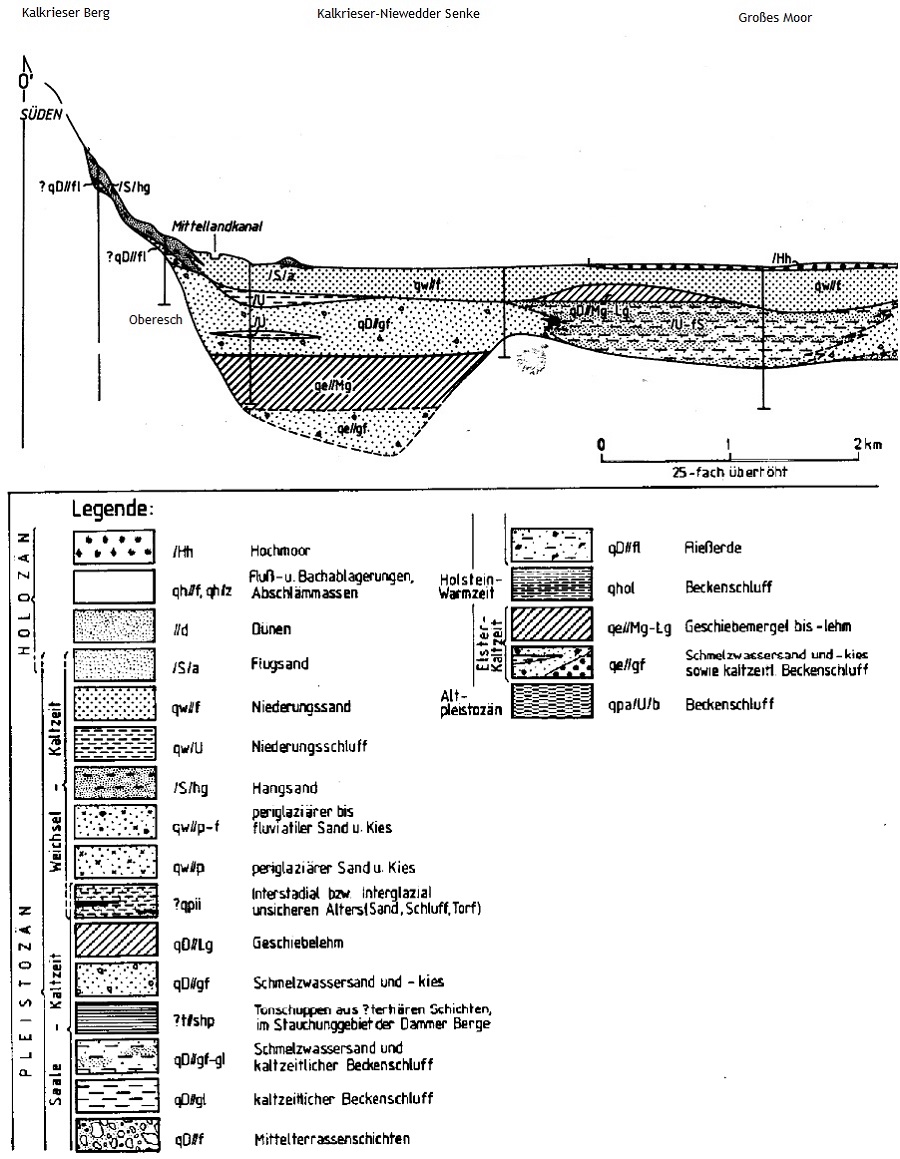

The soil map of Lower Saxony shows that the environment of Kalkriese mainly consists of relatively moist gley soils, on which the Romans were additionally at a disadvantage because of the weight of their armor. However there was relatively dry and firm ground in the area of the ‘Hellweg unter dem Berg’ along a quicksand ridge, today ‘Alte Heerstraße’, and because of the relatively high mounds of bedrock directly below the Kalkriese hill, today ‘Venner Straße’.

Fig. E.2-1a: Geologic profile of the Kalkriese-Niewedde depression (Mengeling, H. (1986): Geologische Karte von Niedersachsen 1 : 25 000, Erl. Blatt 3514 Vörden. – 125 S., 35 Abb., 5 Tab., 7 Kt.; Hannover)

In addition to the flank cover serving combating the Germani on the Oberesch wall, which for this reason was strafed with torsion guns, the Romans attacked the the Germani in westerly direction in two spearheads, as discussed along corridors along the ‘Alte Heerstraße’ and the ‘Venner Straße’. The goal was the encirclement of the Germanic warriors.

Fig. E.2-2: Battle of the Angrivarian Wall Roman attack (blue), resistance of the Germani (red), Oberesch wall construction (brown), peat bog (yellow), Kalkriese hill (green)

Due to the intense fighting along the corridors of the ‘Alte Heerstraße’ and the ‘Venner Straße’ there should also diverse and numerous finds of Roman military equipment to be expected, which is confirmed by the distribution of sites with Roman finds.

Fig. E.2-3: Distribution of sites with Roman finds in the Kalkriese area

The distribution of the finds does not indicate that the two Roman attack groups could unite and the encirclement of the Germanic warriors thus succeeded. Therefore it can be concluded, that the Germani in face of the impending defeat succeeded to escape from the site of battle, and to avoid the encirclement. Thus the Romans were the winners the Battle of the Angrivarian Wall, however it was not a sustainable victory.

Since it can not be assumed that the Germanicus army encamped in the Kalkriese-Niewedde depression while the Germani built the Oberesch wall, it can be concluded that the Romans had to cover a certain march distance to the battlefield. Thus the battle began at the earliest in the late morning. The size of the battlefield suggests that the battle lasted for a while, thus the battle ended in the afternoon. As the Romans searched the battlefield for their own wounded and killed, there was no time to march further, and the field camp for the following night was built on the spot. Thus in the immediate vicinity of the battlefield in the Kalkriese-Niewedde depression there should be traces of a Roman field camp. Due to the soils which had been swept up by the fighting, it might have been advantageous to place the field camp directly on the northern slope of the Kalkriese hill, since the slope gave a natural drainage to the camp. For this purpose, the Germanic wall on the Oberesch would have been planished in the area of the camp. A trench-wall system of Roman construction north of the Oberesch wall, discovered in the summer of 2016, could correspond to the northern wall of a so placed field camp. Thus the northern wall should be located directly at the foot of the Kalkrieser mountain, where the slope passes into the plain (thus at the level of the red mark in the attached graphic).

For the time immediately following the Battle of the Angrivarian Wall, Tacitus reported on a punitive action against the Angrivarii: “Shortly afterwards he [Germanicus] commissioned Stertinius to open hostilities against the Angrivarii, unless they forestalled him by surrender. And they did, in fact, come to their knees, refusing nothing, and were forgiven all." (Annals 2,22) This is another indication of the special importance that the Angrivarii had for the battle, namely the construction of the tactical wall that limited the battlefield, and that caused great hardship to the Romans during the battle.