Annex A: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest between Paderborn Plateau and Haar

Note: If you do not want to work your way through the entire Appendix A immediately (which the author somehow understands), here is a brief summary of the most important information in the Appendix.

A.1 The information availabe for the localization of the Teutoburg Forest Battle

Starting point for the localization of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest is the infrastructure of the province Germania Magna as described in ‘2. Roads’. Especially the location of the legionary fortress Aliso in the present Unna is an important indication of the site of the battle.

As the survivors of the Varus Battle fled to Aliso, Aliso must have been somewhere on the way between the site of the battle and the Rhine, as possible directly west of the battlefield, since this direction was the shortest for an escape to the Rhine. This means in reverse, that the location of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest is situated east of Unna. If this location would had been situated further north or further south, from there it would have been closer the Rhine than to Unna, and the escape to Aliso/Unna would have been a detour.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.1-1: Area to be considered for the location of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest (blue) east of Aliso/Unna (yellow)

Furthermore, ancient sources on the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest have to be considered, so by Tacitus and Cassius Dio (Wikipedia: Sources). Especially Cassius Dio reports in detail, he appears to have the most accurate information about the battle. We learn the following:

- Varus left together with 3 legions inclusive auxiliary troops and baggage a camp at the river Weser in direction to the winter camp

- Varus received information about a smaller, regional uprising of a Germanic tribe and made on his way to his actual destination a detour through uncharted territory to end this uprising

- the detour was an ambush prepared by the Germani, and a battle started

- the area where the battle took place was known to the Romans as SALTUS TEUTOBURGIENSIS and was located not far from the distant Bructeri

- the area consisted in large part of primeval forest, ravines and led through there; in this area, there were swamps and bog soils; the Romans had to cut down trees and build causeways

- heavy rain soaked the soil additionally

- caused by the terrain the marching column of the Romans was stretched far

- the Germani first attacked the end of the marching column, taking advantage of a range of hills

- the fighting lasted for 4 days

- on the evening of the 1st day of the battle, the Romans set up a camp under difficult circumstances on a wooded hill

- from there the Romans moved on, after they had burned the equipment carried in the baggage including the wagons, and reached a clearing

- the Romans set up a well constructed camp

- on the 3rd day of the battle the Romans moved on and again had to pass through a confusing forest area with heavy losses

- the Romans set up a second, smaller and not very well constructed camp

- the Germani concentrated in the course of hostilities more and more warriors and finally surrounded the Romans

- the surviving Romans withdrew to Aliso

- in addition: the first of the revenge campaigns of Germanicus as a follow of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest was waged in the autumn of 14 AD against the tribe of the Marsi, who had participated in Arminius’ rebellion; the Marsi were annihilated in a kind of genocide (Wikipedia: Germanicus); subsequently also Mattium, one of the main Cities of the Chatti participating also in Arminius’ rebellion, was destroyed by Germanicus in 15 AD, after the inhabitants had fled into the forests (Wikipedia: Chatti)

A.2 Determination of the location of the summer camp

Varus planned to lead the 3 legions from the summer camp at the river Weser back to the winter camp in Unna/Aliso. Therefore, when searching for the location of the camp, one must first ask, which section of the river Weser in the year 9 AD the Romans had military importance.

As the Romans probably at first have secured the economically interesting regions of Germania, ie the large Loess plains, which had already developed agriculturally also by the local population, the Weser Uplands and there the Loess areas was one of the first occupation goals. The section of the Weser between the foothills of the Warburg Boerde at Beverungen and the Boerde areas of the Ravensberg Basin near Bad Oeynhausen should therefore have been considered secured military by 9 AD.

The next target was the for agriculture also very favorable north German Plain. The control of the North German Plain was probably the purpose of the Roman camps in Porta Westfalica and Wilkenburg. Since the provincialism of the North German Plain in the year 9 AD was probably not completed, the camps already discovered or yet to be discovered in the North German Plain probably have been Varus’ summer camps, in the winter the Romans retreated back into easier to be supplied camps near to the Rhine.

An ideal location for Varus’ summer camp would have been a centrally located ford across the main river in the North German Plain west of the Elbe, thus the Weser. These requirements would have been well met by Nienburg. Nienburg was first mentioned in 1025 as Nienburch, meaning ‘new castle’, what points to a much older fortification in Nienburg, possibly to a 1025 still visible trench-wall construstion of the Romans.

A.3 Determination of the insurrectionary tribe

Arminius therefore had to come up with a good reason to to lure away Varus from the route. A small regional uprising lend itself very well to this. If suddenly over 20 000 Roman soldiers appear, a small uprising collapses immediately without any fighting. Varus would appear without much effort is in a positive light (on pure development work in the province one can not write such an exciting report for his boss in Rome).

Further it wouldn’t have been possible to get across major military actions to the soldiers at the end of the military season in the fall.

Thus Varus was ready to make a detour from the planned route. However for the detour it was valid:

- The way could not be too far, Varus therefore had to have a clear goal in mind, which could be reached in an acceptable time. Thus the Romans had to know the settlement area of the alleged insurrectionary tribe.

- The way had to be topologically natured in that way, that Varus’ marching column was stretched, which allowed because of the thinned ranks of the Romans a fight man against man.

For Arminius it was therefore necessary to find a decoy (thus the supposedly insurrectionary tribe respectively also the tribe that felt threatened by the insurgents), to which a route with the above criteria led. Since this tribe respectively these tribes have played a decisive role in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, the hatred of the Romans on these tribes must have been correspondingly high, which would have made very probable exceptional actions of the Romans against these tribes during the revenge campaigns of Germanicus.

Good clues to determine these tribes therefore provides the answer to the following question:

Why the Marsi?

Why the Marsi were in the extermination campaigns of Germanicus as first attacked and annihilated so brutally? Why was the next attack against the Chatti? Why didn’t Germanicus combat the tribes involved in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest one by one starting from the Rhine? The latter yet somehow would have been logical. From all tribes involved in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest the settlement area of the Marsi was pretty much the furthest away from the Rhine, thus the attack on the Marsi resembled more like a commando operation deep behind enemy lines than a beginning of a war to sustainable suppression of the uprising.

The answer is that this proceeding simply corresponded to the Roman mentality. The Romans felt deeply hurt in their pride and wanted first to take revenge at the place of the ignominious defeat. Furthermore it should be clearly demonstrated to the Germani that they had to reckon again with the Romans in Germania, and that the Romans would not, shocked by the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, never again enter the forests of Germania.

By the Battle of the Harzhorn another revenge campaign similar to a commando operation became known, in which the Romans pursuited the Alemanni after their invasion in the Roman Empire in the year 233/234 deep into Germania.

A.4 Determination of the location of the ambush

Looking closely at the settlements of the Marsi and the Chatti, is quickly to realize that they have well met Arminius’ above mentioned criteria for the ambush.

The Romans knew the settlement area of the Marsi between upper Lippe and upper Ruhr. The settlement area of the Chatti bordered to the south of that of the Marsi, core areas were the plain of Fritzlar-Waber and the west Hesse depression down to the Giessen Basin, from 15 AD then also the Kassel basin. From Varus’ summer camp at the Weser River, near Minden in particular (see A.2) just as well as from other possible locations for the summer camp, the ancient highway system called ‘Frankfurter Weg‘ since the middle Ages, also called ‘Via Regia’, a since the antiquity well-known tin and amber route from Bremen to Frankfurt via Minden and Paderborn, leads through the settlement areas of the Marsi and Chatti.

Note: You can also see the Senne Hellweg as part of the ancient highway system Frankfurter Weg. In the Middle Ages, the Frankfurter Weg came from the north through the Weserbergland only at the Doerenschlucht on the Senne, but the detour via the Bielefelder Pass would have had advantages for the Roman military. The Senne Hellweg is a trail on a slope, which means solid ground by high-lying bedrock, and by the slope of a natural drainage. On such a subsoil, only one layer of gravel must be applied for the construction of a Via Militaris, and even in the precipitation-rich Roman warm period 3 legions can march in a row from the North German plain towards Paderborn to the intersection with the Westphalian Hellweg and the Haarweg, without the way having been no longer usable on a rainy day after the first 1,000 legionaries and 20 bullock carts. The Romans of course would have been technically able to build the Via Militaris that was following the Frankfurter Weg directly through the Weserbergland (because of the draft animals preferably through the valleys) without the detour via Bielefeld, but then they would have had, due to the drainage, higher costs for both the construction and also the maintenance. The discovery of the Roman camp Sennestadt is an indication of a Roman Via Militaris on the course of the Senner Hellweg. The Roman camp Sennestadt offered space for three legions with auxiliary troops and the baggage, which corresponds to the troop strength of the Varus baggage.

Southward along the Senner Hellweg (Sennerandstraße) at a distance of 15 Roman miles (22.2 km), which corresponds to the average daily marching distance of a Roman legion, there are indications at Oesterholz of another Roman camp.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.4-1: Protohistoric highway ‘Frankfurter Weg’ (brown) via the settlement areas of the Marsi (blue) and the Chatti (red)

Cassius Dio reports that the attack took place in dense forest (“they came upon Varus in the midst of forests by this time almost impenetrable"; Cassius Dio 56,19,5), (“coming through the densest thickets"; Cassius Dio 56, 20, 3). Even though today one cannot determine exactly where there was primeval forests in that area, but one can estimate the probability of the existence of the primeval forest.

In antiquity, because of the not very efficient farming methods those areas were settled at first that were because of the soil relatively easy to cultivate. Areas with Loess soils were thus settled first, which in reverse means that the intervening areas with less productive soils were not settled, and non-settlement or non-cultivationof the soil in Central Europe is usually accompanied by the spread of forest areas. If you look on the Soil Map at the soils of the region concerned, it can be seen, that the Paderborn Plateau mainly consists of flat brown earth, clayey-silty flow soil and limestone and dolomite weathering material. Flat brown soils are usually of low nutrient supply and usable field capacity, nowadays they are mostly used for forestry. As natural vegetation under the prevailing climate on brown earth mixed forests of oak, beech and spruce would appear (Wikipedia: Braunerden). For the eastern Westphalia and the northern Hesse thus it can be deduced, that the settlement centers in the early 1st century were located in the Boerde areas surrounding the Paderborn Plateau (Hellweg Boerde, Warburg Boerde), while the Paderborn Plateau itself was forested.

Thus the first attack on the Roman marching column took place in the primeval forests of Paderborn Plateau.

Fig. A.4-2: Dense mixed forest at the Frankfurter Weg north of Haaren

The main Roman traffic route from Paderborn to the Paderborn plateau led in the direction of Lichtenau and on to Warburg. With the creek Ellerbach only a small body of water had to be crossed, furthermore there was always enough water available on the way to Thuringia along the creek Sauer.

Due to the lack of water supply on the western part of the Paderborn plateau, also coming from the west the Romans chose the way via Lichtenau and Warburg. To avoid the detour via Paderborn on the way to Lichtenau, there was a Roman connection road between Tudorf and Dörenhagen.

The place name ‘Am Roemerberge‘ (at the Roman hill) near Doerenhagen shows that there was a Roman base in this place at the intersection of the main traffic route from Paderborn to Thuringia and the connectinon road from the Haarweg, or that Roman legions frequently camped here.

The connection road crossed the Altenau valley at Etteln. Etteln had the advantage of a firm subsoil, since the Altenau regularly falls dry during the summer months between Etteln and Gellinghausen.

Since the Marsi were not supposed insurrectionary, but probably as allies even had called for Varus’ help against the Chatti, Varus considered himself in the territory of the Marsi in friendly territory. For one, he thereby obviously waived a thorough own, that is Roman recon, and relied on the cavalry of the Germanic auxiliary troops, making the surprise attack by the Germani possible. Secondly, he agreed thereby also the very loose and extended marching order, which was necessary for the crossing of the dense forest areas of the Paderborn Plateau, and that enabled the disastrous defeat of the Romans.

Because of the betrayal of allies, and especially on the territory of allies, in retrospect the Romans were pretty peeved especially about the Marsi.

A.5 The course of the battle

From the topography of the area between the Paderborn Plateau and the Haar and some basic military considerations conclusions on the course of battle can be drawn.

Day 1

The starting point of the battle was a camp in at ‘Am Roemerberge‘ bei Doerenhagen. The reason for this is that Varus wanted to cross the dense and for setting up a camp not suitable forest of the Paderborn Plateau as quickly as possible, and thus not wanted to waste a part of the first day’s march with the advance to this forest.

After the morning roll call and the dismantling of the camp, the marching column marched off in direction of the Paderborn Plateau. After crossing the valley of the Altenau at Etteln, at Kattenecke a gentle slope led onto the plateau in the direction of Haaren.

It is assumed, that the marching column, which comprised 3 legions, 3 Alae (equestrian units) and 6 cohorts with a total of 15,000 to 20,000 soldiers, additionally 4,000 to 5,000 horse, draft- and pack animals, must have been a total of 15 to 20 km in length (Wikipedia: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest). Since such a baggage could hardly have moved through a dense forest with more than 5 km / h, the march onto the Paderborn Plateau has lasted several hours. Added to this was, that also the construction of the causeways, which was due to the entrained wagons necessary at least for the crossing of the Alme river south of Alfen for the advancement of the baggage, probably costed a lot of time.

In the early afternoon, also the end of the marching column was completely in the forest of the Paderborn Plateau.The front part of the at least 15 km long marching column had already crossed a huge part of the plateau, and was located south of the Herssweg on the Sintfeld. At this time the Germani were on the whole route of the Roman marching column in an optimal attack position.

The attack was especially effective where it was possible to force the Romans down a slope or a ravine at the attack, which is why the most fierce attacks took place above the Altenau valley, the Totengrund (ground of the dead), the Taubengrund (ground of the deaf) and the Rohrergrund. The most optimal attack positions were at Haaren above the Totengrund and the Taubengrund, since here the Frankfurter Weg actually led directly above the slope, which is why the Romans found the most wounded and killed at the Totengrund and the Taubengrund (which indeed the place names Totengrund and Taubengrund testify, taub = deaf with the meaning dead).

Note: The Roman historian Appian of Alexandria reports in The Spanish Wars 13, 63, that the Lusitanian army leader Viriathus defeated the Romans at the Battle of Tribola 147 BC in the same way (attack on a Roman marching column from the dense forest and subsequent forcing of the Romans into an abyss). Arminius may have been inspired by these incidents when preparing for his ambush for Varus.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationThe Germani stormed out of the dense forests and entangled the Legionnaires from the stretched marching column in single combats, which the Romans were mostly could not match for. Additionally there was wet and swampy ground in large parts of the combat zone. The incipient heavy rain then made the situation even worse for the Romans.

Explicitly, Cassius Dio in 56, 20, 1-5 also describes the occurrence of particularly violent storms along with the breaking off of treetops, which indicates a wind-exposed location of the site of the Teutoburg Forest battle. In fact, the Paderborn plateau nowadays is being used intensively for the production of wind energy: Sintfeld wind park.

Fig. A.5-2: Wind park on the Paderborner Plateau at Etteln (TIM Online)

Due to the shallowness of the soils on the Paderborner plateau on high-lying lime bedrock not only the treetops break during storms, very often even whole trees fall over there. Due to the high frequency of falling trees, dense undergrowth can develop everywhere, which is not the case to the same extent in forests with normal generation change times of the trees. Thus also in this respect the Paderborn plateau offered ideal conditions for an ambush.

Fig. A.5-3: Root of a on shallow soil fallen tree on the Paderborn plateau

Note: Due to the wind-exposed location and the nutrient-poor soils of the Paderborn plateau, nothing good is to be expected for the condition of metallic remains of the Teutoburg Forest battle. The limestone shards liberated from the bedrock by the roots to a certain extent grind the metal objects. Due to the lack of nutrients and the accompanying lack of bacteria in the soil, a relatively large amount of oxygen is available for oxidation. For these reasons, both by corrosion and mechanically destroyed metal finds are to be expected for the Teutoburg Forest battle. Small metal objects such as sandal nails are no longer to be expected, as evidenced by the absence of sandal nails in the Roman camp Kneblinghausen, which can be explained by nothing else than corrosion.

Since it was a rainy September day, in the northern Sauerland (without the daylight saving time) it was latest by 7 a. m. pitch-dark, and the fighting were discontinued.

For Arminius the result of the 1st combat day was ambivalent. The Germani had afflicted the Romans pretty much, but they had not defeated them. Since it would hardly have been Arminius’ plan to battle several days battle against the Romans, but to defeat the Romans in a surprise attack, he had missed his target first of all, and had to revise his strategy. Consequently, also the Germanic warriors were equipped only for one day, and had to withdraw in the direction of the Hellweg Boerde and to victual themselves at the end of the first day.

The Romans used the combat break to re-establish the communication in the marching column, and by default a camp for the night was set up. It was logistically advantageous to concentrate the baggage in the middle of the battle area at Haaren at the Totengrund and the Taubengrund, especially since the Romans had to take care of the most wounded here. An easila to be defended hill would have been advantageous for the camp, such as the hill fort Knickenhagen offered, which might have its origin in the provisional Roman field camp.

Cassius Dio describes the setting up of a camp under difficult circumstances on a wooded hill (“so far as that [the setting up of the camp] was possible on a wooded hill".

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.5-4: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest Day 1 evening, setting up of a field camp by the Romans in the middle of the combat area ar Haaren (blue), retreat of the Germani towards the Hellweg Boerde (red)

According to old traditions on the Salmesfeld at Haaren a golden legion eagle was found (Arminiusforschung: Goldadlerfund in Haaren?).

According to Tacitus, Germanicus received a legion eagle from the Brukeri (Ann. I, 60), another legion eagle from the Marsi (Ann II, 25). Both tribes were involved in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, and the whereabouts of legion eagles among these tribes are comprehensible.

About the recovery of the 3rd Legion eagle in 41 Cassius Dio reports: “This same year [41], however, Sulpicius Galba overcame the Chatti, and Publius Gabinius conquered the Cauchia and as a crowning achievement recovered a legion eagle, the only one that still remained in the hands of the enemy from Varus’ disaster. Thanks to the exploits of these two men Claudius now received the well-merited title of imperator.”

Thus the 3rd legion eagle remained for 30 years with the Chauci without to be molten and to be processed to jewelry. Further be noted that on the one hand it is unknown wether the Chauci were ever involved in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, and that on the other hand finding the legion eagle made the victory over the Chauci perfect and made it easier for Claudius to accept the title Imperator. Certain doubts as to whether the legion eagle brought from the territory of the Chauci really originated from the Varus legions seem to be justified.

Age determination of the battlefield

The closing coins are the Gaius-Lucius silver deniers (embossing period 2 BC to 1 AD), found at Neuboeddeken above the Totengrund and Taubengrund, finds of later Roman coins are not known. Thus the battle at Haaren took place after the year 1 AD.

Day 2

Cassius Dio describes that the Romans on Day 2 of the fighting came to a clearing and set up camp there, on the way there they were again attacked by the Germani (Cassius Dio: “though they did not get off without loss"). In the clearing, most likely again a camp was set up by default for the night. Since this was in a clearing, the setting up of the camp shouldn’t have been difficult to do, accordingly high the quality of the installation should have been, whereby possibly until today remains of the camp have been preserved. Tacitus also reports on such well set up camp: “Varus’ first camp, with its broad sweep and measured spaces for officers and eagles, advertised the labours of three legions." Tacitus speaks of the firstcamp of Varus which should have been because Tacitus’ informant hadn’t considered the camp of the first day on the woodded hill as a camp. It is also conceivable that due to the vast battlefield Germanicus has not visited all places of battle, and Tacitus reports of the first camp that Germanicus has visited, but which was actually the second field camp. Due to the casualties of the first two days of the battle, on the evening of 2 Day the Romans actually have no longer needed a camp for 3 legions. But since the actual casualty figures certainly were not known exactly, and the Romans also had no time to figure out for how many soldiers the camp at the 2nd evening actually had to be designed, it was set up by default for 3 legions. Probably also with the disadvantage, that defense system consisting of trench and wall actually was overstretched for the number of legionnaires available for defense.

This camp would be located west of the combat area in the Alme Valley, because after the attack by the Germani Varus’ only logical strategy would have been to march west towards Aliso. In fact, west of the Paderborn Plateau at Kneblinghausen there is such a camp on the hill at the streets Romecke / Am Roemerlager (Livius: Roman camp Kneblinghausen), due to non-existent remains of a palisade wall the camp has to be classified as a field camp, it was originally about 450 m × 245 m and was used only very briefly, and it was shortened by 130 m in the east. Probably it was also set up on a Germanic settlement that was destroyed by the camp. The purpose of the camp is not known (LWL: Roemerlager Kneblinghausen).

Thus the Romans set up the field camp at Kneblinghausen by default at the end of the 2nd day of the battle. The way to Kneblinghausen led from Haaren along the Herssweg to the west, with the crossing of the Afte near Hegensdorf and the Alme near Siddinghausen, in order to reach on the Kneblinghausen Plateau one of the routes of the ‘Haarweg’, a prehistoric highway via the Haar. On the plateau between Hegensdorf and Siddinghausen and on the Kneblinghausen Plateau the Germani again encountered the Romans, after they had moved towards the Romans after the night in the Hellweg Boerde. Due to the several kilometers long route of advance from the Hellweg Boerde the attack on the Romans on the 2nd day began in the late morning, and the battle lasted several hours.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.5-5: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest Day 2, Roman withdrawal (blue) to the west, attacks of the Germani (red)

The Germani retreated at the end of the 2nd day for the purpose of food back to the Hellweg Boerde, the Romans used the time until nightfall for the further advance towards west and finally reached the Kneblinghausen plateau. To avoid clearing work the camp at Kneblinghausen was set up in the clearing of the Germanic village which was destroyed by the construction of the camp. With the original dimension of 450 mx 245 m the camp could accommodate about three legions; a field camp for 3 legions, which would not have been created under combat conditions would probably have been a bit bigger.

The smelting of iron mentioned in chapter 1.1 could be the reason why it was possible the Romans in the otherwise wooded area to set up field camp Kneblinghausen. For smelting large quantities of wood are needed, so the area at Kneblinghausen was probably deforested large-scale, which allowed the westward escaping Romans to set up such a large field camp.

Also the field name of location of the camp of the 2nd day, ‘Romecke’ (Rome Corner), could point to an area economically developed by the Romans, s. chapter 1.4. ‘Romecke’ is the Sandhi-Form of ‘Rombecke’ resp. ‘Rombach’, meaning ‘Rom-stream’. On the other hand, the proto-Germanic root word *rēm= ro *rōm= means dust, soot or dirt (Tower of Babel: *rōm= ), all things which result if ore is smelted. Romecke could therefore also mean soot stream and indicate ancient evironment-pollution.

Fig. A.5-6: Rise from the Alme valley to the Kneblinghausen plateau

Fig. A.5-7: Hill of the Roman field camp at Romecke / Kneblinghausen

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.5-8: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest Day 2 evening, Roman withdrawal (blue) to the west, setting up of the field camp Kneblinghausen (brown), retreat of the Germani towards the Hellweg Boerde (red)

When the Roman camp at the end of the 2nd day was completed and the entire Roman marching column had arrived in Kneblinghausen, it became apparent that the camp was oversized with regard to the number of surviving legionaries: the number of legionaries was no longer sufficiently high to guard or defend trench and wall of the camp, and on the other hand to enable the legionnaires also a sleep break. For this reason, the east side the camp was shortened by 130 m, and the circumference of the camp accordingly reduced.

Day 3

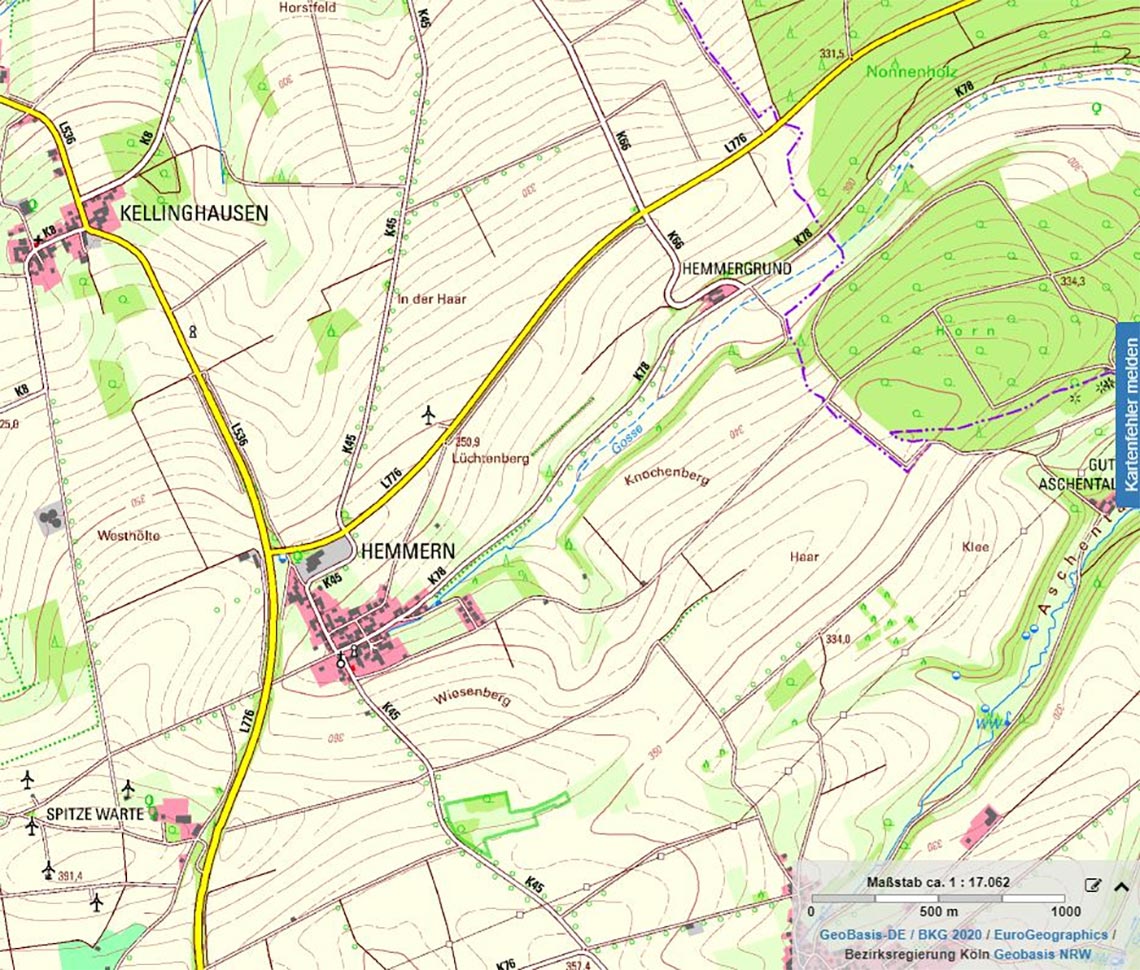

From Kneblinghausen the fastest way to Aliso led westward across the section of the ancient highway ‘Haarweg’ south of the Spitze Warte towards the Haar. The Roman camp near Vierhausen (see Chapter 3.4) shows, that the Romans used the Haarweg as a transport route. Since the Haar was forested until the Middle Ages (Wikipedia: Haar), after the filed camp at Kneblinghausen the Romans again had to cross a wooded area, which is also confirmed in the ancient sources.

Fig. A.5-9: Section of the ancient highway Haarweg south of the Spitze Warte (Map of 1836, TIM-online)

On the 3rd day the Germanic warriors had only a very brief route of advance from the Hellweg Boerde to the Roman marching column on the Haarweg and could attack the Romans throughout the day from. Due to the proximity of the Haarweg to the nucleus of population Hellweg Boerde also further Germanic warriors could attack the Romans, which did not belong to Arminius’ army and were actually busy with the harvesting, but also were willing to break the harvest for a day or two due to the promise of booty when attacking the Romans. The ancient sources confirm that in the course of the fighting an increasing number of Germanic warriors attacked the Romans.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.5-10: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest Day 3, march of the Romans westward via the Haarweg (blue), attack of the Germani (red)

After several hours of fighting, at the end of the 3rd day the Germani again withdraw to night camps in the Hellweg Boerde. The Romans advanced further westwards until nightfall, approximately as far as Drewer. The march distance of 10 kilometers between Kneblinghausen and Drewer likely also the maximum distance that a Roman marching column could advance under constant attack by Germanic warriors. In Drewer also again fresh water was available for the Romans with the source of the Dumbecke.

Near to Drewer the Romans set up again a camp by default. A Roman field camp has not yet been discovered here, however, this might be quite difficult. When setting up the camp, the Romans obviously haven’t put great effort in this, Tacitus reports that Germanicus found only a half-collapsed wall and a low trench in the year 15, which was set up by the battered remnants of the legions (Tacitus, Ann. I, 61).

Note: The place name Drewer could like the place name of the deserted village Drever at Salzkotten be explained by the Treveresgau, which could together with the place name Welschenbeck south of Drewer indicate to activities of Treverian auxiliary troops (e. g. watchfort) during the occupation in this area (s. chap. 1.4), which could explain the clearing on which to the Roman field camp could be set up on the otherwise forested Haar.

Day 4

On the morning of the 4th day, the Romans continued their way to the west / Aliso on the Haarweg, but were again attacked by the Germani from the beginning of the day.

About this time of the looming defeat of the Romans the Roman historian Velleius Paterculus reports, that the Roman cavalry under the legate Numonius Vala fled and deserted, however this escape failed: “Vala Numonius, lieutenant of Varus, who, in the rest of his life, had been an inoffensive and an honourable man, also set a fearful example in that he left the infantry unprotected by the cavalry and in flight tried to reach the Rhine with his squadrons of horse. But fortune avenged his act, for he did not survive those whom he had abandoned, but died in the act of deserting them.”

The failed escape indicates that it was not possible the Roman cavalry, to break through the enemy lines, because after the break through nothing had stood in the way to a escape towards the Rhine/Aliso. As at the elimination of the cavalry a large number of horses were killed, and then decayed in place, it could be that the large amount of horse bones would be reflected locally in a place name. In fact, north of Muelheim at the Haarweg at Taubeneiche there is a place called ‘Pferdefriedhof‘ (horse cemetery), thus it can be concluded that the Roman cavalry on the morning of the 4th split from the infantry and then moved westward on the Haarweg, but then was stopped and defeated by the Germani on a slope of the Haarweg at the Pferdefriedhof.

Fig. A.5-11: Slope of the Haarweg at the Pferdefriedhof

For the Roman infantry which had fought its way to the Pferdefriedhof short time later, the sight of the annihilated cavalry must have been additionally extremely demotivating.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.5-12: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest Day 4 morning, march of the Romans westward via the Haarweg (blue), attack of the Germani (red), escape of the Roman cavalry under Numonius Vala (green)

As the ancient sources report, it resulted with the Romans a big crush and a siege. Arminius had thus managed to stop the Romans on their march and to encircle them. The opportunity to do this was given at the slope of the Haarweg westwards at Taubeneiche. Further the place name Taubeneiche (= oak of the dead) today still points to the hostilities.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.5-13: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest Day 4 afternoon, encirclement of the Romans (blue) by the Germani (red) at Taubeneiche

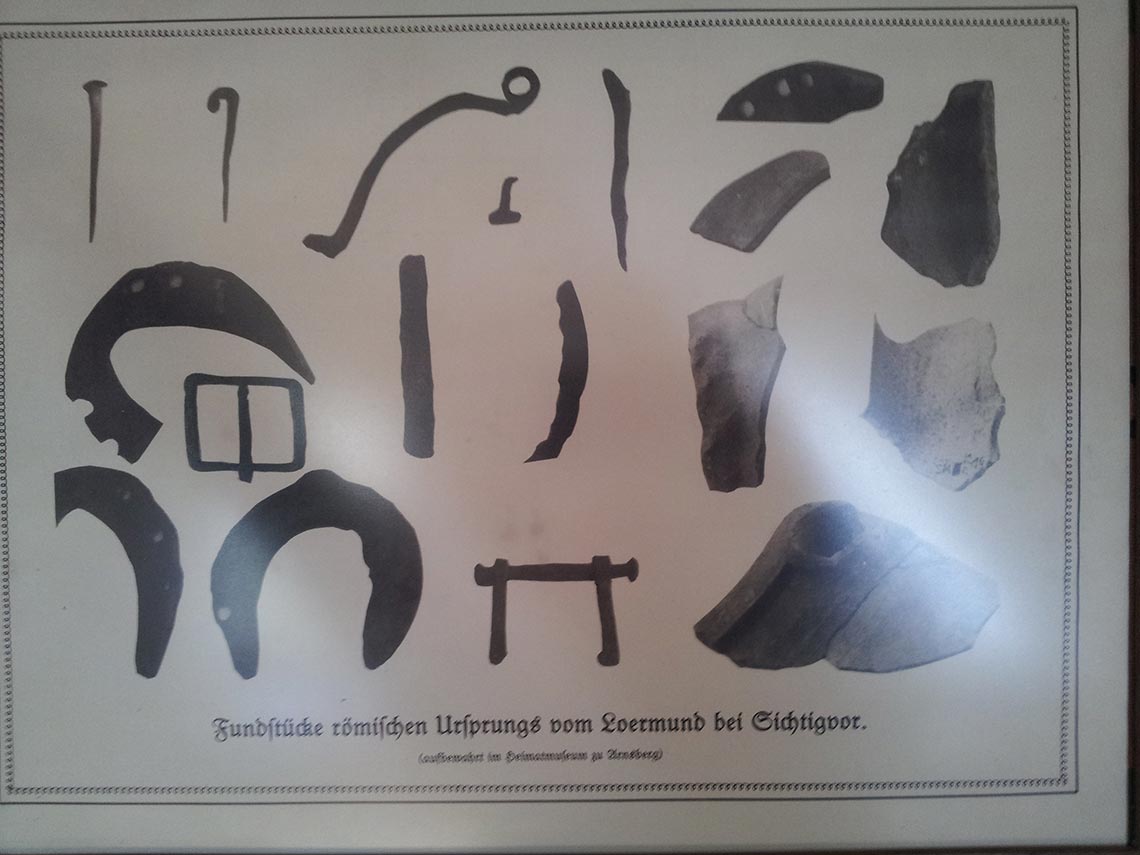

After the battle, the Germans captured the Romans and looted the battlefield. Due to the resulting transport of the booty, Roman finds should to be expected near to the battlefield. The Roman finds at the foot of the Loermund hill at Sichtigvor confirm this.

Particularly local historian Fritz Schmidt († 2017) from Sichtigvor explored the traces of the Teutoburg Forest Battle around the hill fort on the ‘Loermund’ and in the valley of Sichtigvor, and had collected many archaeological artefacts over the decades.

Fig. A.5-14: Archaeological artefacts from the Loermund at Sichtigvor

For the course of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, it results from a starting point at the ‘Frankfurter Weg’ north of the Paderborn Plateau approximately as follows:

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationWith this determination of the location of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest also the background of the campaign of Germanicus in the autumn of 14 AD against the Marsi becomes clear. The purpose of the unfavorable target of the campaign, the tribe of the Marsi far from the Rhine deep in hostile Germania, and the unfavorable time of the campaign in the autumn, where virtually all military activities were ended, was to set an example on the 5th anniversary of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest at the site of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest.

A.6 The connection with the Saltus Teutoburgiensis mentioned by Tacitus as the site of the battle

The Latin word ‘Saltus’ in English means ‘wooded mountains’.

In ‘Teutoburgiensis’ in the Indo-European root ‘teuta’ included, which has the meaning ‘folk’ or ‘people’ (Wikipedia: Deutsch_(Etymologie)).

‘Burg’ has in the German language the meaning of ‘castle’.

Thus the Latin word ‘Teutoburg’ means ‘people’s castle’, and was adopted by the Romans from the Germanic language. People’s castles respectively hill forts are fortifications, often built on hills and consisting of an earth wall and incorporated wall of palisades, in which the local population could retreat at risk of war (Wikipedia: Hill Fort).

A Saltus Teutoburgiensis therefore are wooded mountains, where there are also need to be one or more hill forts. In fact, there is a hill fort near tp each of the combat areas of the Teutoburg Forest Battle.

Above the Valley of the Altenaus between Etteln and Gellinghausen there is the Hill Fort Gellinghausen.

North of Haaren there is the Hill Fort ‚Knickenhagen‘ (Wikipedia: Haaren).

Fig. A.6-1: Wall of the hill fort (Teutoburg) Knickenhagen

On the Loermund above the Moehne Valley at Sichtigvor there is the Hill Fort with the same name (Wikipedia: Loermund).

Fig. A.6-2: Wall of the hill fort (Teutoburg) Loermund – Wolfgang Poguntke, Wallburg Loermund-1, CC BY-SA 3.0

A.7 The grave mound built by Germanicus

According to Tacitus, Germanicus set up a grave mound for the fallen soldiers of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest nearby: “And so, six years after the fatal field, a Roman army, present on the ground, buried the bones of the three legions; and no man knew whether he consigned to earth the remains of a stranger or a kinsman, but all thought of all as friends and members of one family, and, with anger rising against the enemy, mourned at once and hated. At the erection of the funeral-mound the Caesar laid the first sod, paying a dear tribute to the departed, and associating himself with the grief of those around him." (Tacitus I 62)

In this grave mound in 15 AD Germanicus let bury the remains are fallen of the Teutoburg Forest Battle, which means in the hill the remains of an estimated 10000 to 20000 people were collected, correspondingly large and imposing was the hill. For Germanicus’ soldiers the setting up the grave mound was a pretty depressing and demoralizing task, accordingly Germanicus was also criticized by Tiberius: “But Tiberius disapproved, possibly because he put an invidious construction on all acts of Germanicus, possibly because he held that the sight of the unburied dead must have given the army less alacrity for battle and more respect for the enemy, while a commander, invested with the augurate and administering the most venerable rites of religion, ought to have avoided all contact with a funeral ceremony". (Tacitus I 62)

Furthermore, Tacitus reports that the grave mound was destroyed by the Germans again in the further course of the war: “Still, they had demolished the funeral mound just raised in memory of the Varian legions,as well as an old altar set up to Drusus." (Tacitus II 7). As with the ‘destruction’ of the hill probably a desecration and looting of it was meant, and not its removal to the original ground level, the remains of the grave mound should still to be found near the combat area .

To determine the location of the hill, it is advisable to impute to Germanicus because of his Roman mentality very practical reasons for selecting the location of the grave mound. The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest was a four-day march battle, onto a corresponding large area of the bones of the fallen have distributed, that is large parts of the area between the Paderborn Plateau and the Haar:

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.7-1: Combat area of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest on which the remains of the fallen were distributed (blue); approximate middle of the combat area near to the Haarweg southwest of Bueren / east of Hemmern (red)

To keep the effort in collecting the remains as low as possible, a location for the grave mound aproxemately in the middle of the combat zone would have been advantageous, that is in about southwest of Bueren. Since Germanicus wanted to honor the memory of the fallen with the grave mound, the hill also had to be apparent, so he had to be located near a road where people passed and could see it well. Thus the grave mound was located near the main traffic route of that area, the ‘Haarweg’.

After the destruction of the grave mound then, over a long period human remains were scattered around the grave mound, or came over the years until their final decomposition also repeatedly to the daylight, what is possibly still reflected today in a corresponding place- or field name.

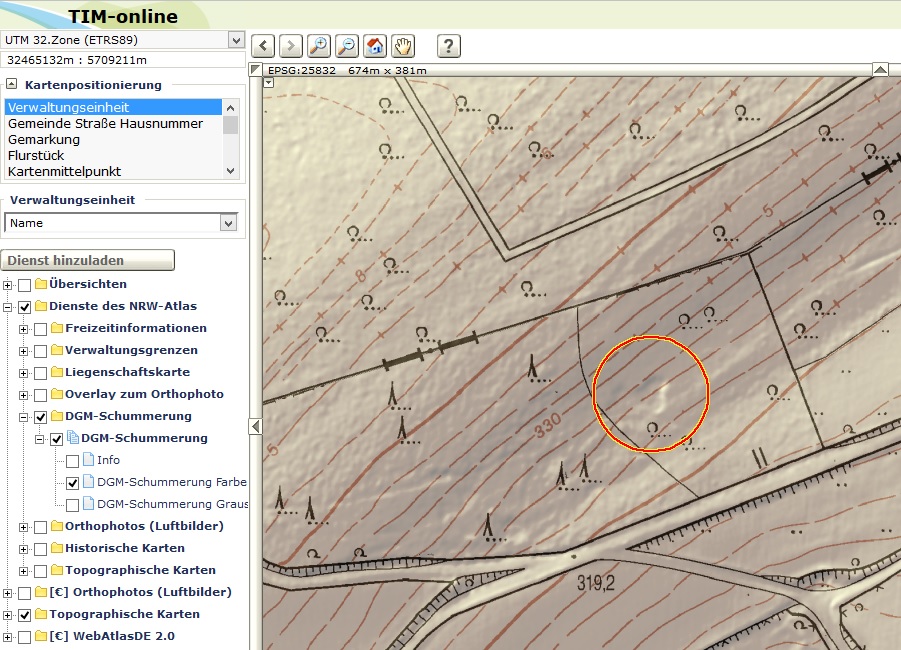

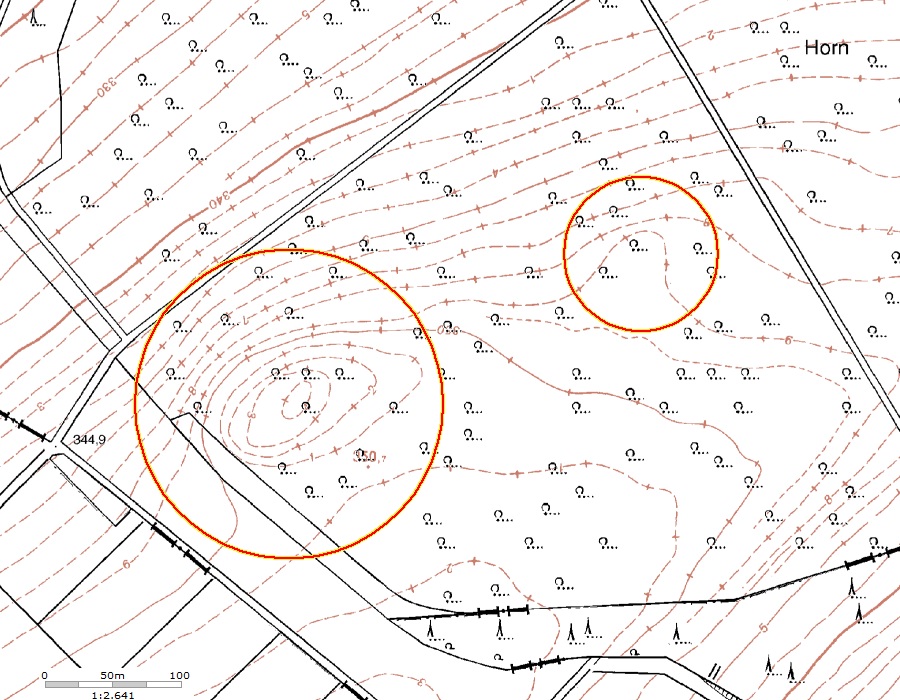

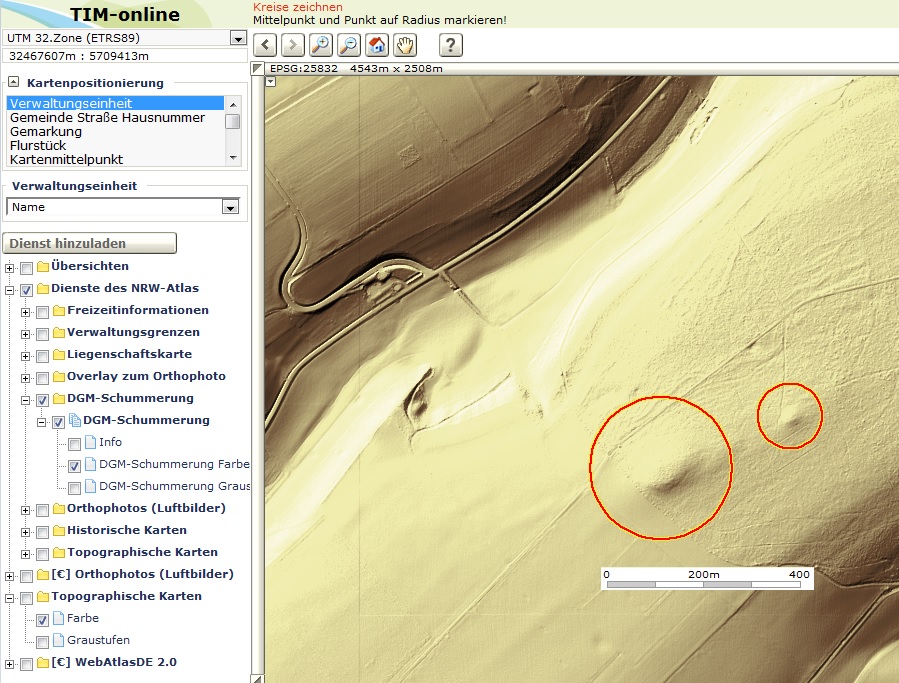

A place that meets the above criteria for the location is the ‘Knochenberg‘ (Bone Hill) east of the fort ‘Spitze Warte’ (section 3.2) at Hemmern:

Fig. A.7-2: ‘Knochenberg’ (Bone Hill) east of Hemmern (TIM-online)

On the ‘Knochenberg’ there is a hill:

Fig. A.7-3: Hill on the Knochenberg

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationVid. A.7-4: Hill on the Knochenberg

Fig. A.7-5: Hill on the Knochenberg

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationVid. A.7-6: Hill on the Knochenberg

The shape of the hill is oval, it is about 120 m long and 80 m wide, the height is about 7 m. The longer side of the hill is aligned with the Haarweg.

A sample revealed that the hill and the surrounding area of the hill consist of different soils. While one finds whitish-gray soil in the area around the hill, the hill itself consists of yellowish soil, partly marbled reddish.

Fig. A.7-7: Soil of the hill

Fig. A.7-8: Soil around the hill

Thus the hill on the ‘Knochenberg’ corresponds with high probability to the grave mound built by Germanicus for the fallen soldiers of the 17th, 18th and 19th legion.

The soil for the grave mound was removed with a high probability on the south side of the ‘Knochenberg’ above the ‘Aschetalweg’ (ash valley road). There you can still see the troughs caused by the removal of the soil.

Fig. A.7-9: Trough at the southern slope of the ‘Knochenberg’ above the ‘Aschetal’

Fig. A.7-10: Trough at the southern slope of the ‘Knochenberg’ above the ‘Aschetal’ (TIM-online)

A sample showed that the soil around the troughs is the same yellowish soil like that of the grave mound.

Fig. A.7-11: Soil around the troughs

Besides the large oval hill on the ‘Knochenberg’ there is also a small, round hill, about 20 meters in diameter and 3 m height:

Fig. A.7-12: Presumed Drusus altar

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from YouTube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationVid. A.7-13: Presumed Drusus altar

Tacitus mentions the grave mound built for the legions of Varus and an older altar built for Drusus one after the other, which could possibly indicate a close proximity of the two objects: “Still, they had demolished the funeral mound just raised in memory of the Varian legions, as well as an old altar set up to Drusus. He restored the altar and himself headed the legions in the celebrations in honour of his father; the tumulus it was decided not to reconstruct." (Tacitus II 7) It is therefore be examined whether the smaller hill on the ‘Knochenberg’ could correspond to the remains of the altar built to Drusus.

Fig. A.7-14: Varus grave mound (large circle), presumed Drusus altar (small circle) (TIM-online)

Fig. A.7-15: Varus grave mound and presumed Drusus altar (TIM-online)

When looking from the ‘Haarweg’ on the ‘Knochenberg’ one can still clearly see the Varus grave mound in the course of the line of the treetops:

Fig. A.7-16: View from the ‘Haarweg’ on the ‘Knochenberg’ (Bone Hill) with the Varus grave mound (red arrow)

On top of which indicates a very shallow groundarus grave mound (and only there) stone fragments can be found, which indicates a very shallow ground.

Fig. A.7-17: Uprooted trees on the grave mound

Between the torn out roots of the fallen trees in this area of the grave mound there are limestone fragments, which have often geometric shapes.

Fig. A.7-18: Torn out tree root on the grave mound

Fig. A.7-19: Torn out tree root on the grave mound

Fig. A.7-20: 90° angle forming stone fragment from the grave mound

Despite the many erosion-related break edges, the stones still have a cuboid structure in principle:

Fig. A.7-21: Principal cuboid structure of the stones in the grave mound with erosion-related fractures

On the flanks of the burial mound there are only rarely stormy falls of trees. If a tree falls because of a storm, in the roots there are not the limestones which are principally there on the top of the grave mound, but only the distinctive yellowish loamy soil of the hill.

Fig. A.7-22: Torn out tree root on the flank of the grave mound

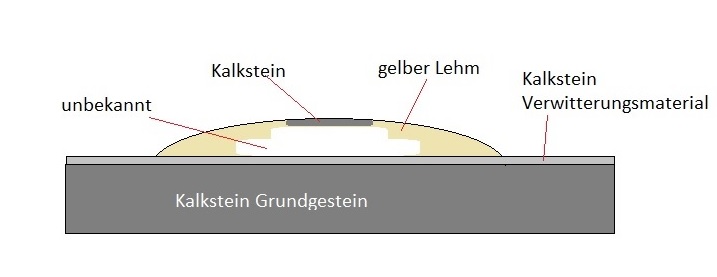

The structure of the grave mound is thus as follows: on a level of gray limestone weathering material on lime bedrock there is a hill of yellowish loamy soil, on the top of which is a layer of limestone. The interior of the grave mound is still unknown.

Fig. A.7-23: Structure of the Varus grave mound, lime bedrock (Kalkstein Grundgestein), limestone weathering material (Kalkstein Verwitterungsmaterial), yellowish loamy soil (gelber Lehm), limestone (Kalkstein), unknown (unbekannt)

The author considered it as a good idea to study the unknown area of the grave mound by means of a non-invasive geo-electric survey of the cross section of the hill, which was completely free of charge for the state of North Rhine-Westphalia because the author would have funded it. However, the state of North Rhine-Westphalia has refused to approve the survey. The author was quite surprised.

A.8 The grave mounds of the Germani

Since also the Germani suffered casualties during the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, and it was due to the number of casualties logistically difficult and due to the several days lasting combats, the subsequent looting of the battlefield, and the subsequent several days lasting march home because of the incipient decay for hygiene reasons impossible to transport the killed Germanic warriors to their own tribal territory and to bury them there, as already described by Friedrich Koehler [“Wo war die Varusschlacht? Neue Forschungen und Entdeckungen von Friedrich Köhler", Ruhfus Verlag Dortmund, 1925] Germanic grave mounds located near to the battlefield are another important indicator of the location of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Since most Germanic warriors likely have died in the attack on the Paderborn Plateau due to the at this time still very powerful Roman soldiers, many Germanic graves should be found at the Via Regia. Actually there is a Germanic burial ground located 5 kilometers north of Haaren right on the Via Regia.

Fig. A.8-1: Germanic grave mound at the Frankfurter Weg north of Haaren

Fig. A.8-2: Germanic grave mound at the Frankfurter Weg north of Haaren

Also in the other combat areas of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest there are Germanic grave mound fields, e. g. in the Altenruethen Forest:

Fig. A.8-3: Germanic grave mound in the Altenruethen Forest

Fig. A.8-4: Germanic grave mound on the hill of the Etteler Ort

The following hill on a spur above the Moehne Valley at Sichtigvor could also correspond to a Germanic grave mound:

Fig. A.8-5: Presumed germanic grave mound above the Moehne valley at Sichtigvor

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationVid. A.8-6: Presumed germanic grave mound

The hill is circular, with a diameter of about 12 to 15 m and a height of about 3 m. A sample revealed that the hill and the surrounding area of the hill consist of different soils. While one finds whitish-gray, partly marbled reddish soil in the area around the hill, the hill itself consists of yellowish soil.

Fig. A.8-7: Soil of the hill (left) and around the hill (right)

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationA.9 The sacred groves of the Germani

The Roman historian Tacitus describes that the captured Roman officers were killed in sacred groves (ie Germanic places of worship) near the battlefield: “In the neighbouring groves stood the savage altars at which they had slaughtered the tribunes and chief centurions." (Tacitus, Ann. I, 61)

As the Romans surrenderd only on the 4th day of the battle, the sacred groves therefore also were located near the battlefield of the 4th day at the Haarweg at Taubeneiche. The question of what made this area unique and thus why it became a place of worship of the Germani could be answered the weather phenomenon of the so-called Sauerland foehn wind:

“The Sauerland foehn wind is a phenomenon which occurs on the northern edge of the Sauerland. Here occur in the small effects like the foehn wind at the Alps. At southern winds, the wind streams against the Siegerland, here it is forced to go up. After the main ridge of the mountain, which lies on the border between the Sauerland and Siegen-Wittgenstein, the air sinks again. Because of this descent, the air warms and dries, thereby clouds dissolve or weaken the rain (Lee). At the Stimmstamm a final ridge is passed, then the air sinks into the Hellweg Boerde. As a result, the air can warm and dry even more. This results usually in cloud gaps north of the Stimmstamm, while it is still cloudy south. By this weather here it is much warmer than in the Siegerland. In these weather conditions, the wind is usually very strong and even in the nights the wind is rarely weaker." (www.belecke-wetter.de)

For a more precise determination of the location of the sacred groves the settlement areas of the local population have to be considered and the distances, that the people were willing to travel for regular ritual acts. Thus at least some sacred groves must have been located near the settlement areas. If you set the population center of the time in the fertile Hellweg Boerde and the location of the battlefield of the 4th day at Taubeneiche in relation, a possible location for a sacred grove would be the Moehne valley dircetly south of Taubeneiche, thus at Sichtigvor. Evidence for a place of worship here are the hill fort Loermund (chap. A.6) and the Germanic grave mound (chap. A.8) in the direct proximity.

Etymological considerations

A sanctuary with the background of the Sauerland foehn wind, thus strong wind currents, could be associated with a Germanic wind deity. In this context, the multiple occurrences of the place name ‘Puesterberg’ in this region attracts attention, e. g. the Puesterberg southwest of the battlefild of the 4th day / northwest of Warstein. The Püsterich is as the name says also related to air currents and could have been a Germanic tin god.

The old name of Sichtigvor is ‘Teiplaß’ (Sichtigvor.de | Geschichte). ‘Tei’ is regarding the pronunciation equal to ‘Thij’, the Dutch name for a Thiestaette(z. B. Thijplein, Rossum, Niederlande). Thus the name ‘Teiplaß’ could indicate a ‘Thie’, whereby a Thie has also served cultic activities in pre-Christian times.

A.10 Verification of the theorie

The combat areas of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest are now used for agriculture and forestry, both agriculture and forestry endanger or destroy objects of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest that have been preserved in the ground. In the context of agriculture, the objects are endangered by plowing, the high proportion of lime fragments in the soil of the Paderborn plateau exposes the objects when plowing high mechanical stresses, they are virtually crushed. In the context of forestry, the increasing degree of mechanization endangers the objects, the soil compaction caused by heavy timber harvesters destroys finds and findings. Therefore, it was necessary to prove the correctness of the theory by means of random samples, in order to sensitize agriculture and forestry that one works on a ground monument.

Favorable sites for taking samples were forest areas, because potential soil finds were not endangered by one millennium of agriculture here. Furthermore, a place above a ravine favored the discovery of potential soil finds, because here, as described above, the most violent attacks were to be expected. On the basis of these criteria, 2 sample areas were selected, one at the Nonnenbusch on the slope below the ‘Etteler Ort’, another on the slope above the ‘Totengrund’. As predicted theoretically, there are a high number of metal objects in the ground in these locations, the fund density increases in each case in the direction of the slope:

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.10-1: Find distribution ‘Totengrund’, theoretically determined combat area (red), sample area (blue), finds (red points)

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Google Maps. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationFig. A.10-2: Find distribution ‘Nonnenbusch’, theoretically determined combat area (red), sample area (blue), finds (red points)

The found metal objects are basically in a very bad condition, they are badly corroded and hardly magnetic anymore:

Fig. A.10-3: Metal objects found at the ‘Totengrund’, on the left one end of a stylus

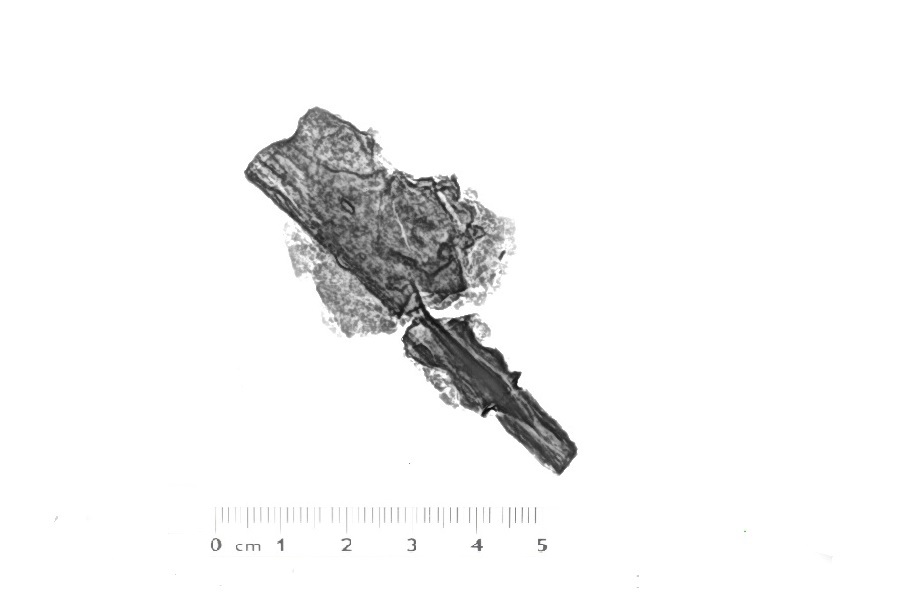

Even on the x-ray, only approximate structures could be recognized:

Fig. A.10-4: X-ray image of a metal object found at the ‘Totengrund’ (end of a stylus)

And even the restoration produced almost no identifiable objects. However a determinable object among the very limited amount of samples was the spatula-shaped flattened end of a stylus, cf. the early imperial period Roman stylus shape group A 12 in „Forschungen in Augst, Band 45/1, Verena Schaltenbrand Obrecht, Stilus“, p. 116 und in „Forschungen in Augst, Band 45/2, Verena Schaltenbrand Obrecht, Stilus“, p. 351:

Fig. A.10-5: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest find, restored flattened end of a stylus, ferroalloy (higher resolution)

Another determinable object is a fire striker in a form that was already used by the Romans:

Fig. A.10-6: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest find, restored fire striker with pry and diagenesis of a leather lining, ferroalloy (higher resolution)

Other determinable objects are fragments of a knife and a belt buckle:

Fig. A.10-7: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest find, restored fragment of a knife and diagenesis of the leather lining, ferroalloy (higher resolution)

Fig. A.10-8: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest find, restored belt buckle with thorn, ferroalloy (higher resolution)

The discovery of a Celtic spout hatchet can also be classified in the context of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. It could have been lost by a member of the Celtic auxiliaries of the Romans.

Fig. A.10-9: Battle of the Teutoburg Forest find, Celtic spout hatchet

Important evidence for the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest: finds in several places

The next step in verifying the theory would be a metallurgical examination of the finds from Totengrund and Nonnenbusch, similar to what was carried out in the years 2017 to 2022 for the finds from Kalkriese (Mining Museum Bochum: research project on the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest). If the metallurgical examination would show that the metallurgical signature of the finds from the battle areas at Totengrund and at Nonnenbusch is the same (the signature would not even have to be assignable to a specific legion), this would show that the battle events at both locations are connected, and indicate a march battle. Since no other march battles from the Roman-Germanic war are known apart from the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, this would be a very strong indication that the events on the Paderborn plateau were the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. Since all attempts of the author to establish contact for cooperation have been ignored by the scientists involved in the topic for years, the author is under no illusions that such an metallurgical examination could take place in the foreseeable future. But, it would be now exactly the right next step.

There are many other metal objects in the soil iof the sample areas. For the protection of the earth monuments the author advises still to archaeological investigations and to a careful agriculture and forestry in the above-described combat zones of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest.

Fig. A.10-10: Avoidable devastations in the area of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest